What’s Old Is New Again

Snowmobiling tends to occasionally recycle good ideas for better times.

Call us jaded. Call us unimaginative and unappreciative. Whatever you want to call us, sometimes we have reasons for being less than overwhelmed with bright, new advances in snowmobiling technology. One of those reasons comes from having seen some of the latest and greatest “new” ideas a few decades earlier. That’s not always the case, but ask particularly inspired vintage sled enthusiasts about modern technology and they may share similar feelings. If you look to past concepts, you may find that snowmobile engineers fought similar battles “back in the day.”

We are not bemoaning the current technologies in snowmobiling. Good gracious not! But, sometimes the ideas of yester-sleds couldn’t succeed because the materials to make the idea viable didn’t exist at the time. Look at how Polaris uses its “super glue” techniques to bond pieces of its newest sleds together sans rivets and welds. The technique makes the current sleds lighter and actually tighter than previous methods. But those materials weren’t available in the 1970s.

The fact that early Arctic Cat Panthers used lightweight riveted aluminum tunnels proves that snowmobile engineers looked for the best ways to build light sleds. Where Polaris’ modern bonding techniques comes from the auto industry, Arctic Cat engineers borrowed from aircraft building techniques of the time.

Back in the day — my how that sounds s-o-o old! — snowmobilers suffered some problems that since have been solved. Thankfully! In the late 1960s and through the 1970s, snowmobile tracks could unroll off a sled at any inconvenient time, laying down a 10-foot rubber carpet. That rarely happens to modern sleds, although we bet a few vintage sled riders know what we’re talking about!

The Dahlman Track

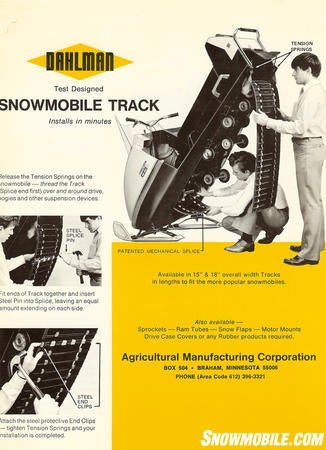

The ability to simply thread the Dahlman Track cut installation time and saved money.

The ability to simply thread the Dahlman Track cut installation time and saved money.

Unlike conventional tracks, the Dahlman design could be installed much more quickly as you didn’t need to remove the drive or bogie wheel assemblies. The Dahlman track could be “threaded” over the drive axle and fed over the bogie or slide assembly because it used a mechanical splice to join the two track ends together. All you needed to do was relieve the sled’s tension springs and thread the splice end first, fit the ends of the track together, insert a special steel pin into the splice and attach steel protective end clips to secure the connection.

The Dahlman track came in 15- and 18-inch widths that would fit the majority of sleds of the time. Another claim to fame was said to be a smoother ride thanks to the use of rubber cushioned steel sprocket lugs.

Despite the “…Improved design of the Dahlman Snowmobile Track,” which was tested in a Los Angeles laboratory, on snow at Mammoth Lakes, California and alfalfa fields in Minnesota, the track didn’t make it. What did make the difference in track longevity were better track materials, such as Aramid fibers, and improved designs. But we do like the idea of not having to remove the drive and suspension components to replace a track as you do with modern one-piece circumferential designs.

Ski Concepts

You may think that concepts like twin track, dual edged skis or hull-shaped, concave skis are current technology, but those ideas have been floating snow since the 1970s.

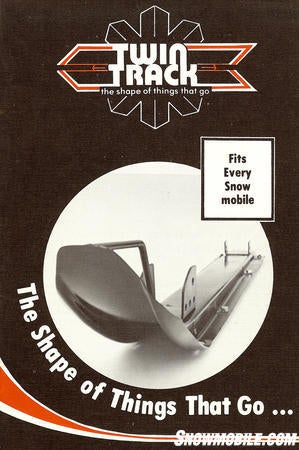

“The shape of things that go…” was the tag line for Twin Track, which billed its design as the “…first breakthrough in snowmobile skis in 20 years.” Twin Track skis came with two edges for more positive ski steering response and control. The designers claimed their ski reduced driver fatigue and said it was like “switching to radials on your car.” Now that was a while ago, as virtually all modern automobiles dropped bias ply in favor of radials decades ago!

Twin Track skis were the “shape of things that go” and featured twin edges for increased steering response and reduced driver fatigue.

Twin Track skis were the “shape of things that go” and featured twin edges for increased steering response and reduced driver fatigue.

Constructed of 14-gauge steel and equipped with a sturdy ski lift handle, the design carried a suggested retail of $79.95 per pair— in today’s money, the skis would retail for more than $295.00.

But, Minnesota-based Twin Track wasn’t the only manufacturer of the time with better ski ideas. Design Unlimited International in Guilford, Connecticut introduced what it called “…A truly significant breakthrough in snowmobile performance.” Called the Dual Ski, the Connecticut group offered its extruded aluminum dual ski at $59.95 per pair.

The Dual Ski featured what its promoters referred to as an “exclusive dual downdraft design.” This tunnel hull concept was borrowed from the boating industry. It was said to push aside snow and ice letting the ski ride atop the snow for easier steering and superior tracking.

Available in a single model, the Dual Ski came with adjustable mounting brackets that could be adapted to fit any sled, with or without shock absorbers. Remember that at the time snowmobiles used leafsprings as trailing arm or A-arm front suspensions were yet to be popularized. The ski also featured a vinyl-covered handgrip at the tip that allowed the snowmobiler to lift or move the ski. A safety nose guard was an option.

Wear Bar Ideas

Of course, if skis and tracks needed re-invention in the 1970s, what about wear bars and control rods? A Toronto-based outfit offered case hardened steel “Sno-Keel” heavy-duty wear bars that they thoroughly tested in the Canadian northlands. Designed for simple bolt-on installation, the Sno-Keel sold for $12.95 per pair in 1974 (equivalent to $60 today).

The Sno-Keel differed from the standard wear bar by featuring a v-shape that would bite into the terrain as opposed to the standard round wear bar. The wear bars were designed for popular models from Ski-Doo, Moto-Ski, Sno-Jet, Boa Ski, Rupp, Polaris, Arctic Cat and Yamaha.

Grass Drags

But not all “in the day” aftermarket products were intended for trail usage. Back in the mid-1970s, summertime snowmobile drag racing was popular. Kalamazoo Engineering offered a drag suspension and track specially designed for turf racing. By 1974 the Michigan-based company had updated its original Sandblaster drag suspension to include a rigid parallel frame and bogie wheels. The previous version was used on a gas-burning 404cc modified Yamaha to set an Ontario speed record of 94 miles per hour! That was fast, back in the day. Not so much today!

The revised Sandblaster II offered more adjustability with a front torque arm that could be adjusted to one of six positions. The suspension also showcased a combination rear shock/traction bar to maintain downward pressure for improved hook up off the starting line.

If you wanted to be competitive, you’d have spun Kalamazoo’s polyurethane TrickTrack grass drag track around the Sandblaster suspension. The track weighed 17-lbs and featured an internal drive. The 103-inch track retailed for $129 in 1974 (that would be equivalent to $602 in today’s dollars).

As you can see, our fathers and uncles cleverly sought solutions to snowmobile performance right from the start. Times aren’t so much different now, what is different is the quality of materials and techniques brought to bear on solving problems. High-tech computer programs and laser-enhanced machines would have been welcomed in decades past to advance new ideas.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices