Power to Fun

Since Day One, the perception of power rules, but power to weight remains king

My snowmobiling reality may be different than many as I’ve been riding since the mid-1960s. That time frame includes casual trail rides, but also includes competing in at least one serious racing event per decade up to the turn of this new century. That’s where the importance of power-to-weight as a concept caught my attention.

In my earliest riding and competition, it became painfully obvious that weight mattered. You quickly understood the limitations of those early 1965 Ski-Doo Olymique sleds, especially if your racer was the “ten and a half” Olympique with a paltry 10.5 horsepower to power an avoirdupois of 240 pounds or so, plus your own body weight. That certainly made you long for the 12 and 16 horse models.

Early Ski-Doo’s featured Rotax engines that performed well enough, but left huge margins for future power lust.

Each of that 1965 Ski-Doo’s ponies had to lug around more than 22 pounds of dead weight (minus my own). Moving on to the Winnipeg-to-St. Paul cross country event and my stock-as-stock 1977 Polaris TX-L 340 racer, power to weight still mattered, especially as that sled’s then-new liquid-cooled 333cc Fuji twin came with a stock rating of about 55 horsepower. Since it gave away power to the competition, making its power delivery efficient and paying attention to weight mattered. In stock form, the sled weighed in at 405 pounds, but in race trim it added an extra fuel tank plus carbide-tipped studs. And there was some added bracing to make the chassis last over 500 miles of ditch banging.

In basic form, each of the TX-L’s two-stroke twin’s horses carried about 7.5 pounds. That was quite an upgrade from the 1965 Ski-Doo, right? And, actually, when you look at the specifications for a 2018 Chevrolet Corvette Stingray, the TX-L looks good. The Stingray features a 455 horsepower, 6.2 liter V8 to horse around a curb weight of 3298 pounds. Each HP carries 7.2 pounds or close to the weight per horsepower of the 1977 TX-L. Now, according to my handy-dandy “Vehicle Horsepower to Weight Ratio Calculator,” the ‘Vette has a 0.138 horsepower to weight ratio. The TX-L’s ratio using the same calculator is 0.135!

The joint effort between Arctic Cat and Yamaha results in sleds with 200 horsepower and power to weight performance ratios that could sting a modern 455 hp Corvette Stingray.

Of course, back in 1977 the TX-L didn’t seem like a 2018 Corvette. Maybe because the Stingray has 460 lb-ft of torque at 4600 revs and that Polaris twin had negligible torque by comparison.

How do new sleds, like the 2018 Ski-Doo MXZ X 850 E-TEC compare? It’s new 849cc Rotax twin delivers a claimed 165 hp at 7900 revs and weighs in at a claimed 475 pounds. That breaks out as a horsepower-to-weight ratio of 0.3474. Each Rotax horse carries about 2.8 pounds.

Horsepower helps but added to lightweight platforms it creates “hold-on” holeshot launches like this 850cc Ski-Doo.

We can only guesstimate the Yamaha Sidewinder with its 200-something horsepower and guessed at 550-ish weight. Based on 200 hp and a weight of 550 pounds, the horsepower to weight ratio would be 0.3636, with each turbocharged horsepower responsible for 2.75 pounds. Based on those guesses, the Sidewinder’s 998cc turbo four-stroke triple and the Ski-Doo’s 850cc two-stroke twin look responsibly similar.

Of course, the turbo advantage at altitude surpasses the Ski-Doo’s or any other normally aspirated motor, two-stroke or four-stroke. The turbo maintains power where the non-turbo engine drops off as elevation increases. Advantage Yamaha.

Since our days with the old Ski-Doo Olympique, we’ve lusted for power like many of you. But, since the advent of a 200 hp power sled, attaining a more responsible age filled with senior discounts and, most importantly, having survived a near-fatal motorcycle accident not so long ago, our speed and power lust has been mitigated. Yes, the annual snowmobile review tests are wonderful. We can push our limits as we push in the throttle lever on a turbo. We can grab a handful, hold on at a holeshot as the sled’s skis lift and the chassis torques right, and watch triple digits fly by as we cross a mile-wide lake. On that 1965 Ski-Doo we could compose an article. On the Yamaha Sidewinder we’d have trouble composing a useful thought. But it would be a kick!

Yamaha added major firepower to the sport when it added a turbocharged 998cc triple to its line, an immediate “must have” among power hungry riders.

We too often tend to think of performance strictly as horsepower numbers. They count. But how that power gets translated to the track matters. How that power feeds information back to your throttle thumb matters. How your guttural sensations read that power matters. In 1965 any Olympique rider knew that 10.5 horsepower was nowhere near enough. In 2018 more of us recognize that the Sidewinder’s 200 horsepower in a platform that weighs around 500 pounds may be adequate – or, still not enough.

Power numbers count, but horsepower to weight counts more! At least in our view. When we practiced for that so long-ago Winnipeg cross country event, we trained with a Polaris Colt SS 340. It didn’t have the top speed and overall power of the TX-L race sled, but it was lighter, narrower and less stable at top end. The power to weight seemed similar as it served to help us gain experience in the ruts and bumps, bobbing and weaving like a fly weight boxer. As a result, when we ran the race, the TX-L felt planted, more controllable and quicker overall thanks to the training with the Colt. Power mattered, but power to weight and how to use it mattered at least as much.

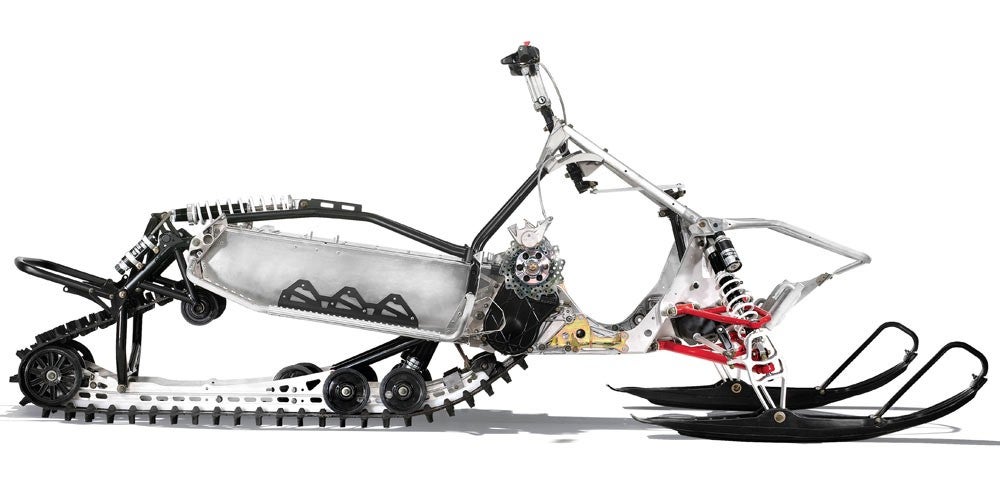

Horsepower is the major factor in creating strong power to weight ratios, but careful sled design plays an equivalent role as seen in the “bare bones” chassis on Polaris’ Rush and Switchback models.

We’ve come quite a way in power from the mid-1960s. We know that some grass drag racers of the past used power and power to weight for victories. Imagine a 200-horsepower motor mounted on a vintage chassis that’s little more than a straight piece of steel with a track and plastic skis. That was the time when now-illegal blends of fuel were commonplace and speeds soared.

For production sleds, it’s not so simple to simply add horsepower. Ask Ski-Doo, which totally reinvented its REV platform and created a next generation E-TEC with greater displacement and performance. Yamaha and Arctic Cat partnered to make room under the hood of the existing Next Gen bodywork platforms to accommodate the triple-cylinder 998cc Genesis turbo. It’s not simple to get big power numbers into a mass-produced snowmobile.

When you do, though, it’s a commandment breaker creating a sledder’s lust for power. Big power in a heavyweight sled? So what! Big power in a properly weighted power to weight sled? Bring it on and let’s squeeze the trigger.

When riding and racing that 1965 Ski-Doo or that 1977 Polaris TX-L, who would have thought that we’d ever have such power and performance in relatively lightweight sleds that could rival the numbers of a high-tech, US$56,000 Corvette Stingray? That’s some upgrade from 10.5 horses, but it’s my 2017 reality!

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices