1971 Grand Prix by Boatel

Uniquely equipped snowmobile wasn’t for everyone

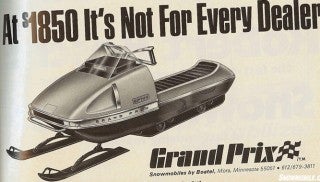

Something unique hit the snowmobile world in the early 1970s, the Grand Prix by Boatel. Not a household name among snowmobilers, Boatel tried to break from the pack of also-rans in 1969 by creating a truly unique model. That unique sled was called the Grand Prix and was not only loaded with features but was loaded with a style all its own. Focusing on uniqueness, Boatel’s advertising slogan was: “Grand Prix—it’s not for everyone.”

Like many snowmobile manufacturers in the early days, Boatel was primarily a builder of things other than snowmobiles. In Boatel’s case, it built houseboats, pontoon boats and trailers. Adding a snowmobile line gave the Mora, Minn.-based company an opportunity to utilize its people and facilities year-round. The added manufacturing of snowmobiles extended the company’s seasonal boat-building and added employment to the local area.

The Ski-Bird

In its first foray into snowmobile manufacturing, Boatel built a contemporary type of sled called the Ski-Bird by Boatel. Like many other small manufacturers, Boatel used ‘off the shelf’ engines from JLO and others. In an attempt to build a name for its brand, Boatel entered Ski-Birds in various racing events, including the fledgling Eagle River closed course and cross-country races in nearby Wisconsin. Despite a smattering of success in racing, Ski-Birds by Boatel failed to capture the public’s imagination like Ski-Doo and Polaris.

In a gamble, Boatel decided to be a trendsetter. It would abandon the Ski-Bird and create a showcase snowmobile with sexy styling and all of the best features a snowmobiler could possibly want. Enter the Grand Prix by Boatel.

That first season the Grand Prix came with just two engine choices: a moderate 434cc Rockwell-JLO fan-cooled twin of 28 horsepower, or a larger 744cc twin with 45 horsepower. The Grand Prix 440 carried a suggested retail price of US$1695 while the Grand Prix 760 sold for US$1,850. By comparison, the ‘760’ cost $500 more than a high performance Ski-Doo with a 640 Rotax. But Boatel was gambling that its uniqueness and fully featured model would be worth the price. After all, they knew the Grand Prix wasn’t for everybody. Their advertising said so.

Boatel sought high volume, successful dealers to market its Grand Prix model.

Boatel sought high volume, successful dealers to market its Grand Prix model.When Boatel approached dealers to handle the new Grand Prix line, the company sought high volume dealers who already carried the top brands such as Arctic Cat, Polaris and Ski-Doo. Boatel sought a limited number of special dealers to carry its new line. They wanted aggressive dealerships, which would be able to move more than 50 units yearly.

By selecting top dealers, Boatel looked to offer such dealers an alternative profit maker that would augment the dealers’ proven brands. When approaching dealers, Boatel emphasized the Grand Prix as “…the industry’s first and only high priced, high performance, high prestige snowmobile.”

Boatel also told dealers that they could expect $200 more profit per sale. The dealer cost for an early Grand Prix 440 was $1,271. In fact, the dealer cost for that Grand Prix was higher than retail pricing for an Arctic Cat Puma with a Kawasaki 440cc twin.

The ‘up’ sell

Chromed skis added to the sled’s rich look—and price.

Chromed skis added to the sled’s rich look—and price. These fighter jet inspired ducts added a performance look.

These fighter jet inspired ducts added a performance look. The unique ‘butterfly’ steering was a signature feature of the Grand Prix snowmobile.

The unique ‘butterfly’ steering was a signature feature of the Grand Prix snowmobile.Dealers were told that the Grand Prix was an excellent opportunity to ‘sell up’ their customers to a more fully featured luxury model. And Boatel’s market research indicated “…there are many consumers across the snowbelt who will pay top dollar for a quality, high prestige snowmobile.” The company asked potential dealers to consider the auto industry where there was a percentage of buyers who buy the finest. Boatel concluded its pitch with “We know it will sell.”

On paper and in its aggressive advertising campaign, the Grand Prix looked like a winner. It was styled in rich gold with chrome accents. There were stylish air intakes on the side of the cowl mimicking the hottest jet fighter aircraft of the time. There were no options. Every feature was standard, including: electric start with a manual rope pull backup; speedometer and tach; fuel reserve in the gas tank; temperature warning light; cigarette lighter; underseat stowage with a tool kit; a padded dash and, even, a snowmobile cover. Unique to the Grand Prix was the ‘butterfly’ steering that replaced the traditional handlebar. The throttle and brake levers were positioned in the steering housing. Added to all of these features were aluminum chassis construction, a 20-inch wide polyurethane track and torsion bar bogie-type suspension.

Bold warranty

In its advertising, Boatel was as bold as the sled’s design. It claimed the Grand Prix was a rare breed with rare qualities. Speed. Lightweight. Stability and dependability were highlighted. And, so too was an incredibly generous warranty. In fact, the Grand Prix warranty was not just better than any existing warranty of the time; it may be better than any current snowmobile warranty.

Boatel stated: “Should you damage your Grand Prix in any way whatsoever–including racing or mishandling—within one year of purchase, we’ll replace all warranteed parts. We’ll do it free during the first six months from date of purchase, and pay 50% of the price of warranted parts during the next six months…”

Of course, Boatel was not stupid. The engine warranty was separate. Boatel simply stated: “Engine, of course, is covered by manufacturer’s warranty.”

Bold claims

This 1971 Grand Prix by Boatel is nearly as new as the day it was turned out at the Isle, Minn. production facility.

This 1971 Grand Prix by Boatel is nearly as new as the day it was turned out at the Isle, Minn. production facility. The Donaldson exhaust effectively quieted the Rockwell-JLO twin.

The Donaldson exhaust effectively quieted the Rockwell-JLO twin.With its appeal to the uncommon snowmobiler, the rider who wanted it all and had the money to get it, the Grand Prix created some interest. According to Boatel’s promotional materials the Grand Prix was a must have sled. It was claimed to have speed. Boatel materials stated: “The high horsepower-to-weight ratio and freer-wheeling drivetrain delivers speeds up to 60 mph with the Grand Prix 440… or up to 80 mph with the Grand Prix 760.”

With its aluminum alloy construction and use of other lightweight materials like polyurethane in the track and Cycolac materials, the Grand Prix was claimed to be 60 pounds lighter than the most common wide tracked sled of the day. The 760 was said to weigh in at just less than 400 pounds. These are claims we see in today’s advertising, so the advertising and marketing world hasn’t changed all that much in four decades.

Unfortunately, when the real world of snowmobile magazine test rides caught up with the Grand Prix, real opinions of riders didn’t totally back up the marketing hyperbole.

In its October 1970 issue, Invitation To Snowmobiling magazine tested a 399cc version of the Grand Prix. They acknowledged its full-featured attributes, calling it plush and quiet. But they also said it was long, wide and heavy— “… a not-too-speedy tourer.” Quoting the company brochure that claimed a top speed of 60 mph; the magazine test staff could only wring 52 mph out of the test unit. Raced against two other brands of similar displacement, the Grand Prix “…netted a glorious third.”

The testers did comment about the sled’s excellent build quality and said that it offered, “…As quiet a ride as you’ll find.” That actually was quite a compliment if you recall how terrifyingly loud some sleds were back in the early 1970s.

Price versus value

The test staff tried to justify the sled’s price tag by pointing out that its underseat storage area held goodies galore like a full tool kit, a quart of oil, machine cover, battery for the standard electric start, spare drive belt and spark plugs.

That unique butterfly handlebar steering did not escape notice. The test riders stated simply that while they were unique and looked great, they didn’t really do anything spectacular in helping you to turn the skis. In fact, they noted, “… You can’t lean out to the side of the GP and whip around.” They did note that the sled was, indeed, stable, saying “It’s the world’s only snowmobile that really hugs the snow—at the expense of turning corners.”

The review agreed that the Grand Prix was unique, but called it pricey and damned it with extremely faint praise. How else do you read the test review’s final comment? “They say it’s not for everyone. Maybe it’s for the family who wants to own a snowmobile, but underneath it all, really hates to get out there and go snowmobiling.” Ouch!

Whatever impact the magazine’s review had, the Boatel Grand Prix had a very short history. It was gone by 1973.

We suggest that it was a victim of being too expensive when compared to the popular brands like Ski-Doo and Arctic Cat. Its pricing may very well have made the competition look pretty good by comparison. And, then there was some serious competition coming from more well know names such as AMF and its Ski-Daddler, Johnson and Evinrude, John Deere, Mercury Marine, Harley-Davidson and the arrival of Yamaha.

The Grand Prix was a high-risk gamble that raised the stakes for a brief period, but eventually failed to pay off for the manufacturer. Boatel did create a uniquely styled snowmobile that may not have been for everyone, but does deserve a moment of remembrance.

Related Reading: The Polaris TX-L Vintage Review: 1974 SnoJet 1968 Sno-Skat

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices